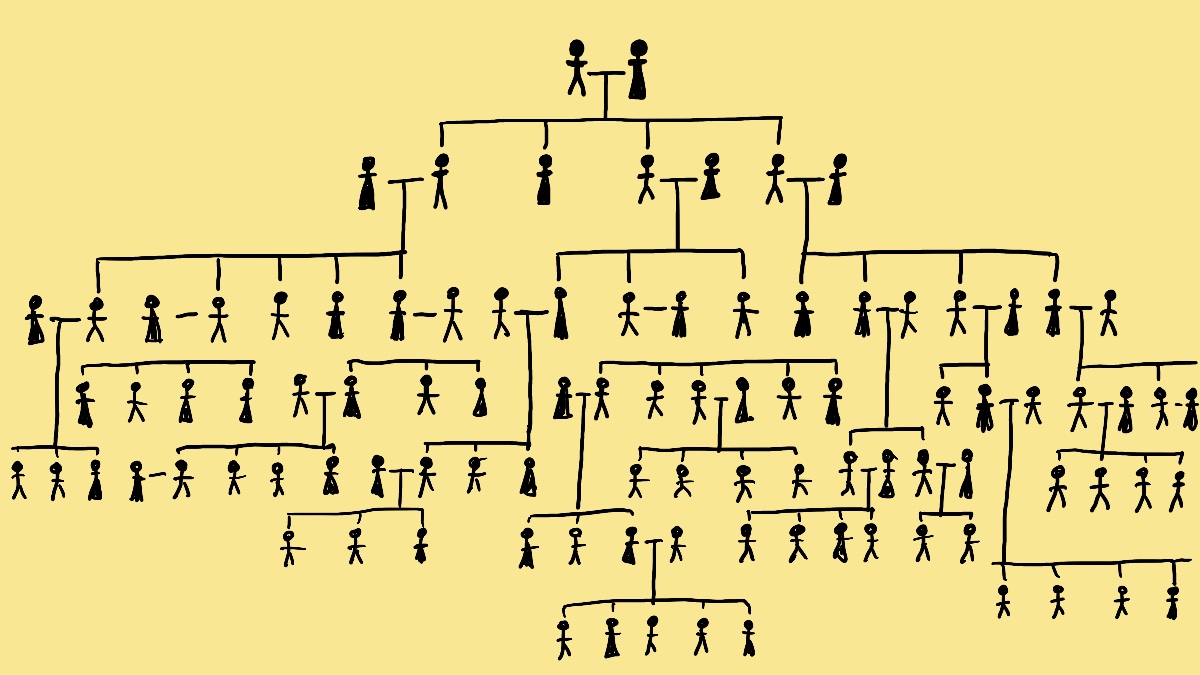

Because there are a number of mediums in which to read (or listen—I’ll just keep referring to reading/listening as reading) a book, the manner in which we read a book can play a role in the way we understand and learn from that book. The following is a hierarchy of the way I categorize mediums for the messages I consume.

0.5 – Podcasts

Let me start first with a kind of honorable mention of sorts—podcasts. Podcasts have functioned for me as a means of curating authors and finding some potential good reads. But this is specifically in the non-Christian and non-fiction genres. Topics or genres like tech, self-help/improvement and productivity, health, and general culture. (I don’t listen to Christian podcasts, although I have in the past.) At the time of writing this, I’m not listening to many podcasts, but that’s the role they used to play. Often, a podcast curator (i.e., someone who interviews people in their field) would introduce me to an author and their topic as a promotion for an upcoming book or something of that nature. If it was sufficiently interesting, I’d then listen to the audiobook—which is the next medium.

Audiobooks

I listen to non-fiction, secular audiobooks. I don’t listen to Christian audiobooks (or not often, or primarily).

My audiobooks come from two providers:

- Audible—which are paid for with a subscription, allowing me to listen and re-listen as much as I want.

- Spotify audiobooks—which I generally start with.

The books I listen to on Spotify are ones I’m vaguely interested in. I’m not committed to listening to them the whole way through, and I often have a lower threshold for attention regarding them. I’m happy to listen for an hour and then stop if it’s not any good or interesting. Or, if I’m wondering whether a book is going to be good, I might listen to an audiobook on Spotify and then buy the audiobook on Audible so that I can re-listen to it and potentially have my wife listen to it as well. Also, I use Spotify to listen to shorter books—I don’t want to spend my Audible subscription listening to short books. It’s less economical. And it also helps me give a certain kind of seriousness to the books I buy on Audible.

Otherwise, I listen to dedicated audiobooks on Audible. As I mentioned, I use Audible for longer audiobooks. They are pretty much all secular books, mostly non-fiction. But Audible is also a place where I read fiction books—long fiction books that are fantasy or something similar. I get a decent bang for my buck—$16 AUD gets me a good 70-hour listen sometimes. And I re-listen to some of them.

A Quick Note: What About Audio bibles?

I listen to audio bible. I have two that are my favorites. My all-time favorite I actually bought on CD years ago. That has since become impossible to manage. But it’s also available on Audible—”Inspired by… The Bible Experience” audio bible on Audible is my favorite version. Although it has had some issues in the past—it sometimes wouldn’t play, and it used to have a terrible ‘chapter’ system that didn’t line up with the Bible chapters (horrible!)—it has since been fixed. That’s my favorite version.

My second favorite is on Spotify (or available on Spotify, but it also has its own app, which is worth supporting, in my opinion). It’s called “Streetlights“ audio Bible. It has a beat behind the audio, and it is technically not an audiobook in Spotify, so you can listen as much as you want (the only downside is you have to make a note of where you’re up to). But I don’t listen to audiobibles often.

…

I listen to audiobooks often—when I drive or travel, when I do house chores, or sometimes when I exercise. In terms of the proportion of ‘reading’ that happens, audiobooks are where it mostly happens for me.

This is something interesting about my hierarchy: In terms of importance, the greatest proportion of books happens in my least important category—audiobooks. I value Christian theology over secular writing, but I listen to a greater proportion of audiobooks compared to other mediums (although I’ve not actually measured this—it’s just my guess).

Why ‘read’ what I consider to be the least important writings in a medium that promotes the most amount of content consumed? That is—why would I use audiobooks to get through more books that I deem to be least important? And why not use audiobooks to listen to more important books or genres like Christian theology?

The answer is in other blog posts.[1] But the short answer is—the medium is the message. You engage more superficially with audiobooks. You get more of an emotional and intuitive sense of the writing and the argument. But in terms of information retention and formation of the mind, the least amount of that occurs under the medium of audio. I want to make sure I get the most retention from theological writing. But before I outline that medium…

E-books

I use my Kindle to read e-books, and the e-books I read are, mostly, fiction books. I read my Kindle before bed, and so I want to unwind. I read fiction books on my Kindle as a way of unwinding before bed.

I used to read—and still sometimes do read—Christian theology on Kindle. But what I’ve found is that it’s difficult to go back to something you read, re-read it, mark it, and write your thoughts down. What I’ve found Kindle to be good at is making big books easy to hold. The Lord of the Rings is huge—literally—in your hand. But it’s as big as a pamphlet on your Kindle. So I try to read some fun fiction as a wind-down on my Kindle. But occasionally, I read a big theology book on Kindle. Occasionally. Something like a history book, which can be unwieldy in paperback, I find helpful on my Kindle.

Paper Books

This is the gold standard.

So obviously, the Bible is the first and most important. Paperback books are where you get the most tactile experience. You get the best retention of information. The best ability to remember where something was written. You can make notes, highlight, and annotate (I think e-versions of notes and highlights are just sub-par imitations).

Otherwise, I read my Christian theology in book format. I mark it up, re-read, highlight, and scribble. I know where all my books are on the shelf. My bookshelf is ordered in a way that represents what books I’ve loved and found most helpful. So I can easily go back to a book I remember well.

Now, if a book I listened to on Spotify was so good I wanted to purchase it, I might buy it on Audible. Or, if an Audible book was very good, then I would buy that book in paperback. So I do have secular paperback books—not many, but some that I absolutely love, like Cal Newport’s work (Digital Minimalism and Slow Productivity). I’ve also loved Matthew Walker’s book on sleep, Why We Sleep. There are some others, but those are notable. I might have listened on Audible, bought it on Kindle, then bought it in paperback.

And you might think I’ve wasted my money. But I’d argue—the medium is the message.

The Purpose of a Hierarchy of Reading Mediums

This hierarchy of reading mediums exists to point out that different mediums provide a very different experience and varied levels of understanding. In one sense, you haven’t read a book if you’ve listened to the audiobook. You’ve skimmed it.

That’s why this hierarchy exists in my mind and practice. I want to take seriously the medium and match it best to the intention and intended outcome of my reading. Reading paperback books is something special for me, so I save it for the most important books. Whereas audiobooks pass the time.

Intentionality is key. So I try not to mix my mediums and intentions.

Related Reading:

McCracken, B. (2021). The wisdom pyramid: Feeding your soul in a post-truth world. Crossway.

Wolf, M. (2018). Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World (1st ed). HarperCollins Publishers.

[1] https://bigvaiandshiphrah.com/2022/06/30/the-reader-and-external-knowledge/, https://bigvaiandshiphrah.com/2022/07/14/the-readers-discipline-of-contemplation/, https://bigvaiandshiphrah.com/2022/07/28/rereading/