Have nothing to do with irreverent, silly myths. Rather train yourself for godliness; for while bodily training is of some value, godliness is of value in every way, as it holds promise for the present life and also for the life to come. (1 Timothy 4:7-8 ESV)

First, spiritual training is essential because it’s benefits are enduring through this life and into the life to come. That gives us an anchoring perspective. But I what to consider physical training. To what extent is it valuable, and in what way?

I want to argue that while physical training is still of lesser value than godliness, it may be comparatively more valuable today than it was in the first century when Paul wrote those words, simply because of the vast differences in lifestyle between then and now. Today we prioritise comfort and convenience lending to the dominance of inactivity and sedentary living in the everyday. Hence the “some value” of physical training might actually carry comparatively ‘more value’ for modern readers.

Godliness

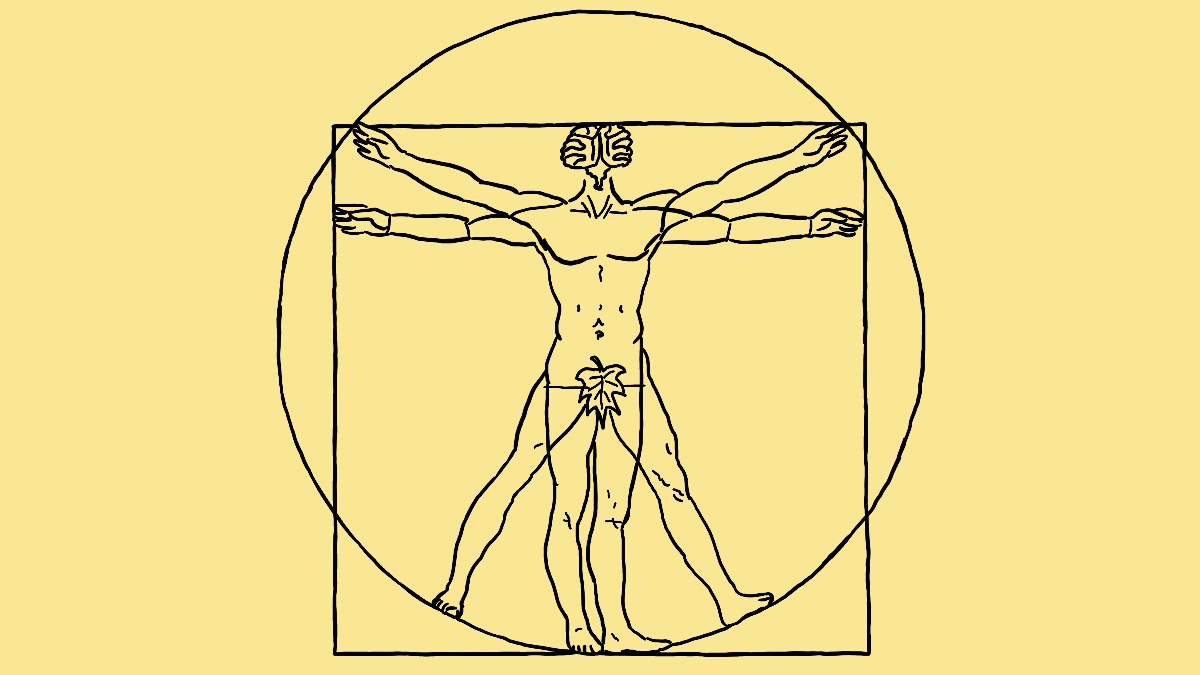

Before considering the minor note of the passage, let me say from the start that the emphasis of the passage is clearly on godliness -we mustn’t skip that step (just like I know you would never dream of skipping arm day). Physical training is ultimately useless to someone unconcerned with godliness because you’ll still be unfit to stand before God. That’s why Paul says, “train yourself for godliness” (v.7). Paul’s metaphor borrows the required practices and personal characteristics of physical training and applies it to the spiritual life so that strength, stamina, focus, and endurance become pictures of what’s required in the pursuit of godliness. If we train spiritually then we are conditioning ourselves to withstand and counter false teaching, godless myths, and all kinds of spiritual opposition. To lean into the mindset of Ephesians 6 for a moment: with greater grip strength, you hold fast to the truth of the gospel; with greater muscle mass, you uphold the weight of sound doctrine; and with better endurance, your character stays firm under prolonged spiritual strain. Godliness is the essential training of the Christian life. See to it that this is where you get the most gains.

Physical Training

But now to physical training. The passage is making a metaphoric comparison, but it is also advocating for the limited but real value of physical training. When Paul says that physical training is of “some value,” he’s not dismissing it as unimportant or trivial. The point is that its value is limited in scope—temporal, not eternal. It’s useful for this present life, but not the next. Like James says, “we are a mist that appears for a little while and then vanishes” (James 4:14). Our bodies develop, peak, and eventually deteriorate. While physical training is not of ultimate value like godliness, it is still valuable—for this whole life! Paul’s emphasis isn’t that it’s value is meagre, but that its benefits don’t extend beyond death.

Paul

Let’s consider the apostle Paul, the one who is writing these words to Timothy (his younger apprentice). If someone tells you that physical training is of some value and they want you to listen, take it on board, put it into practice, then you would need to ask yourself of the credentials of said personal trainer. So consider Paul.

Yarbrough, in his commentary, notes that the scholar Eckhard Schnabel, in his essays on Paul’s missionary work, estimates that Paul may have travelled around 450 kilometres a year on foot—not including time spent in small boats (which is its own kind of arduous work). And Paul did this consistently for roughly 30 years. I’d add to that: Paul’s travel didn’t take place in small, daily increments (i.e., a little walk around the block with 15 minutes in the gym afterward every day). It happened in large chunks—long journeys from point A to point B. And in the in-betweens, he was a tentmaker (Acts 18:3).

Aside from this, Paul himself must have been tough – proper tough – the kind of tough that would make even a Navy SEAL recruiter reach for more OHS forms. In 2 Corinthians 11:23–27, Paul details the countless hardships he endured which is worth quoting in full.

“I have worked much harder, been in prison more frequently, been flogged more severely, and been exposed to death again and again. Five times I received from the Jews the forty lashes minus one. Three times I was beaten with rods, once I was pelted with stones, three times I was shipwrecked, I spent a night and a day in the open sea, I have been constantly on the move. I have been in danger from rivers, in danger from bandits, in danger from my fellow Jews, in danger from Gentiles; in danger in the city, in danger in the country, in danger at sea; and in danger from false believers. I have labored and toiled and have often gone without sleep; I have known hunger and thirst and have often gone without food; I have been cold and naked.” (2 Cor. 11:23–27)

Of course, Paul acknowledges that he was weak and that his endurance was ultimately sustained by God’s grace and miraculous preservation. But from a human perspective, his life and ministry demanded truly extraordinary physical and mental resilience. So we should conclude, Paul is well qualified to say to a ministry apprentice, “physical training has some value”.

The Ancient Context

What about all the other people in Paul’s time? Consider the following.

In The World of the New Testament, David Downs, in his chapter (12) on “Economics, Taxes, and Tithes,” outlines a general picture of life in the Roman economy. (Downs is drawing on Steven Friesen’s “poverty scale” of the Roman economy, published in 2004.) The picture they provide of the Greco-Roman world is that the vast majority of the population lived at or near subsistence level.

Only a tiny fraction belonged to the imperial elite, and just 1% were regional or provincial elites. Urban elites made up about 2% of the population. A small portion (~7%) had moderate surplus resources, while around 22% lived at a stable but vulnerable subsistence level. The largest group—40%—lived at or just below the threshold needed to sustain life, often working as small-scale farmers, laborers, or artisans. An additional 28% lived below the subsistence line, including the poorest in society: widows, orphans, beggars, unskilled day laborers, and prisoners. (It’s worth noting that some scholars argue life may have been marginally better than these figures suggest).

You’ve got to try and keep this in mind when you read the New Testament and imagine its world. Although this kind of socioeconomic breakdown doesn’t give us a day-to-day picture of their labor and activity, it certainly helps us imagine what might have been required just to survive. You could even read a period piece set in the late 1800’s or even early 1900’s to give some perspective. It’s not hard to picture how physically demanding and economically fragile life was for the overwhelming majority of people in the first-century world.

We see similar summaries in other writings, such as Arjan Zuiderhoek’s essay “Work and Labor in the Ancient World”, in which he writes:

“The ancient world, then, was very much a world of work—and hard work at that. Greek and Roman farming populations (and their work animals), as well as urban workers, manufacturers and service providers, had to toil long and hard, day in, day out, to produce the surplus that made possible the impressive material achievements (in terms of urbanisation, infrastructure, art and architecture) and the luxurious lifestyle of the elites of their respective societies. Labour productivity in agriculture was low, which necessitated the employment of the vast majority of the ancient world’s populations in the production of primary foodstuffs, and condemned the vast majority of individuals making up those agrarian populations (as well as a sizeable element of the urban inhabitants) to a standard of living not much above subsistence.” (Zuiderhoek, p. 32)

So, what’s the point here? If life was this physically demanding for so many people, then that’s an interesting context in which to read the words, “physical training is of some value.” It’s not as if people were unfit. On the contrary, they were, by default, laborers and farmers whose diet consisted of the raw, unprocessed produce of their own toil. That required strength, endurance, and resilience. And yet, Paul still says to his apprentice minister: physical training could still be of some value for you.

Today

Today is different. In so, so many ways.

We actually have to exercise in order to move at all sometimes, because modern life can demand as little as 1,000 steps a day—or even less. Inactivity kills us. Overeating kills us. The irony is that we’ve gone beyond subsistence to the point of no longer sustaining health. Our food is so processed that we’ve had to fight legal battles just to call it food.

Consider the latest release (as of 2023) from the Australian Bureau of Statistics:

“Almost one in four (23.9%) people aged 15 years and over met the physical activity guidelines,” and, “Nearly half (46.9%) of employed adults aged 18–64 years described their day at work as mostly sitting.” [ABS – National Health Survey, 2023]

By the way, “exercise” in the 2022 report includes the following:

- “Nearly half (48.5%) walked for exercise,”

- “Nearly half (47.4%) walked for transport,”

- “One in three (32.8%) did moderate exercise,”

- “Three in ten (30.5%) completed strength or toning exercises,”

- “Almost one in five (18.6%) engaged in vigorous exercise.”

[ABS – Physical Activity, 2022]

Today, you actually have to think about “fitness.” In pre-modern times, I doubt anyone thought about it (aside from athletes, I presume). That’s because life simply demanded physical exertion. At this point, let me recommend Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis.

Today, people—and therefore, Christians—have to intentionally consider physical training and its “limited value.” And we must do this while resisting the temptations of modern fitness culture: vanity, body idolatry, and self-worship. Instead, we’re called to simply steward our health for the sake of ministry endurance.

The Christian and Physical Training Today

The Christian minister—whose priority is godliness—should train physically in the modern Western world. I’m assuming you’re one of the statistics in the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Today, it’s easier to be unfit and poorly nourished than to be otherwise.

Geoff Robson, in his book Thank God for Bedtime, makes a point about the relationship between godliness and physical sleep. Building on Don Carson’s observation—“If you are among those who become nasty, cynical, or even full of doubt when you are missing your sleep, you are morally obligated to try to get the sleep you need”—Robson writes:

“If we became aware that eating a certain food caused us to behave in a consistently and predictably sinful manner, we’d stop eating it. If you became aware that wearing a particular shirt somehow made you act in ungodly ways, that shirt would go straight in the trash. So if sleep makes it harder for us to maintain self-control, or to remember what we read in the Bible, or to have the energy to help someone in need, suddenly sleep isn’t just a good idea. It’s a godly idea. It’s vital to living a life worthy of the gospel.” (p. 74-76)

In a similar pattern of thought, I would argue that if you have a godly concern for ministry—and a desire to serve with endurance for the long haul—then you should proactively consider your physical fitness. This is not to dismiss the reality of illness. In fact, you might be given ill health by the Lord—a “thorn in the flesh.” As James reminds us, “If it is the Lord’s will, we will live and do this or that.” But surely, as far as it depends on us, we want to make the most impact over the long term. Physical fitness can serve as a simple, baseline metric for supporting that godly pursuit—not at the exclusion of prayer, reading, and teaching (matters of godliness), but as a tool to enable them more effectively.

Health is something to be stewarded for godly ends. Physical training is one tool we use to manage that stewardship. Avoiding preventable health issues is a basic strategy for maintaining strength and energy for ministry. The goal is simple: to remove the hindrances to faithful service and to have the energy to do the work God has set before us. And that’s not even to mention the cognitive benefits of exercise. For white-collar workers in the knowledge economy—such as ministers—this will only become more and more relevant.

Simply put, Paul would want us to run the race and to work hard in the marathon of ministry. Part of that includes our physical capacity and capability. So why is physical training of some value, but lesser value? Because it serves another purpose—namely, ministry. It serves serving. But if it is lacking, it may well become a hindrance to that ministry. The chief concern is godliness; and flowing from that—though in the background—is the service of others in gospel work: proclamation, discipleship, and the like.

References

Easter, M. (2021). The comfort crisis: Embrace discomfort to reclaim your wild, happy, healthy self. Rodale Books.

Green, J. B., & McDonald, L. M. (Eds.). (2013). The world of the New Testament: Cultural, social, and historical contexts. Baker Academic.

Robson, G. (2019). Thank God for bedtime: What God says about our sleep and why it matters more than you think. Matthias Media.

Yarbrough, R. W. (2018). The letters to Timothy and Titus. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Zuiderhoek, A. (2020). Workers of the ancient world: Analyzing labour in classical antiquity. In A. Bresson, P. F. Bang, & W. Scheidel (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the ancient economy (pp. 32–48). Oxford University Press.