If you or I were to ask a handful of people—church folk or otherwise—whether, loosely speaking, they felt or knew that God had spoken to them personally, my guess is that many would say they think it has happened. For staunch Reformed folk, this idea tends to make us uncomfortable (if that’s you, I know it does! But also, I bet you’ve heard people say these very things to you!). So, how should we think about this phenomenon?[1]

On first principles, we affirm that God primarily speaks through His written word. Very true. Sola Scriptura, baby. Ultimate authority (I’ve written about that here [2]). God’s Spirit is working through God’s Word with God’s power. Even though that proposition and doctrine is firmly established, we still know that much of our work—whether personally or in ministry roles and responsibilities—is continually pointing people back to God’s Word, because both we and others regularly harden our hearts against it (Psalm 95). Not to put a number on it, but for illustration’s sake, let’s say this is 80% of the work.

But even God’s Word tells us that God has spoken outside His written Word.

This is the disciple who testifies to these things and who wrote them down. We know that his testimony is true. Jesus did many other things as well. If every one of them were written down, I suppose that even the whole world would not have room for the books that would be written. (John 21:24-25)

It’s obvious that not every word Jesus ever spoke is recorded. But consider what those words might have been—personal encouragements and challenges to his disciples, words to passersby, rebukes to his opponents, or his mountaintop prayers to the Father. So, clearly, not every word of God is recorded in written form, and yet all of them are the words of God.

I think the Reformed instinct is to lean so heavily on the authority of Scripture (rightly so) that we sometimes develop tunnel vision as an unintended consequence. The words of Scripture are sufficient for salvation and godliness—the essentials. But they are obviously not everything that God has ever spoken or done. This is not problematic or worrying.

We can also assume that the prophets of the Old Testament spoke messages that were not recorded in the Bible. This may be how many of them became recognized as prophets. Then, of course, there are those who were called prophets whom we never hear from, other than a mention of their existence, or whose writings have been lost. In 1 Kings 18:3-16, Obadiah (not the prophet) hides 100 prophets from Jezebel (and Ahab). Yet, we never hear a word from these 100 fugitive prophets. In 1 Kings 13, there is an unusual story of a “man of God” who is a prophet (unnamed) and another unnamed prophet—except he is a false prophet (perhaps that’s why none of his words are recorded). But regardless, he is still referred to as a prophet. Similarly, just like the 100 prophets Obadiah hides, there is a “company of prophets” in 2 Kings 2:1-15 who witness Elijah being taken up in a chariot of fire.

It’s all very interesting… But what about today? I mean, those examples come from back in the day. Times have changed. The Son has spoken definitively (Hebrews 1).

Now we begin to delve into the discussion of continuationism and cessationism. But for the sake of brevity, the best argument I’ve heard for cessationism is that “the time of the apostles and prophets” ended after the apostles passed away. Another argument is that once the “foundation of the apostles and prophets” was laid (Ephesians 2:20), there was no further need for revelation—and no need means no supply. A historical argument is that miracles are not as common anymore as they were in the early church, and if we follow the trajectory, we see them fade away completely after serving their purpose in the initial spreading of the gospel.

For the most part, I’m not convinced that the theological grounds for these arguments are strong enough (although cessationism is a tenable position). It is just as likely—although I’d argue more likely—that when we read the passages of the New Testament, especially those referring to gifts broadly categorized as revelatory gifts (such as prophecy, but depends on your take on what that is), they continue. There isn’t a sunset clause on these passages. So, I think the safest assumption is to presume they continue rather than to assume they have ceased.

At any rate, that would make sense of two things: firstly, anecdotally, people everywhere still claim to hear from or be led by God in personal ways (receiving personal revelation of a sort). And secondly, the Scriptures still tell us to test such things.

“Dear friends, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, because many false prophets have gone out into the world.” (1 John 4:1)

“Do not quench the Spirit. Do not treat prophecies with contempt but test them all; hold on to what is good” (1 Thessalonians 5:19-21)

“Two or three prophets should speak, and the others should weigh carefully what is said.” (1 Corinthians 14:29)

But I don’t think these passages are exclusive or exhaustive in describing how God speaks to us today (biblical revelation notwithstanding). God is certainly able to speak to us more directly (not necessarily corporately)—in dreams or otherwise. That aspect of communication is not necessarily the troublesome part—it’s not a question of whether He can. The issue is knowing when He has—determining and testing these words.

We need to be aware of our own self-deceptive tendencies and the deceitfulness of the heart, as well as the spiritual realities of opposition and deception from the demonic. I think this last point is why we are reluctant to accept personal revelations so easily (speaking personally and anecdotally about the Reformed tendency to be skeptical in this regard). We are very aware of the Scriptures’ warnings, and so we are (hyper?) vigilant when it comes to accounts or claims of personal revelation.

For most of the (let’s call them) inclinations of people who think or disclose that God has spoken to them in some way—especially when it includes a sense of being led to do something—it can be difficult, if not impossible, to know how to test it.

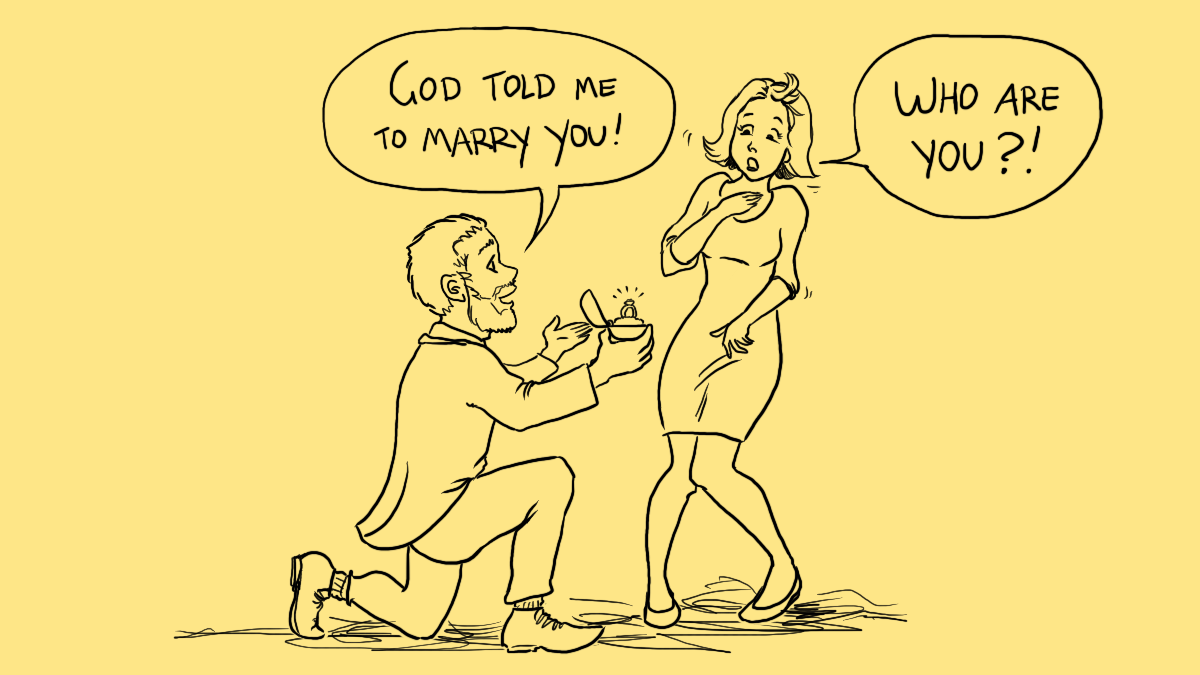

First, it must not contradict Scripture—that’s a given. But what about things that are indifferent? Or even more challenging, what about things that we might not call wrong, but perhaps unwise in principle? For example: “God says, ‘Start a business.’” Or, “God says, ‘Travel here…’” or… hehe… ‘Marry that person!’ I love that one! It’s just too convenient. (Or is it…?)

Especially with these indifferent cases, we have no clear grounds on which to say, “That’s not a message from God—God wouldn’t say that.” You might think such a person is being arrogant in claiming to hear from God, but we can just as easily be arrogant in claiming they didn’t.

God leads us. It’s that simple. His providence is all-encompassing. Nothing is too small or too big to escape His guidance – “You should buy bread today.”, “You should move to this city.”, “Marry them!”

And indeed, God cares for our welfare, but He does not merely or exclusively lead us into prosperity—He refines us as well. Suffering does not automatically mean we were led astray or that we were wrong to consider it a word from God. Likewise, prosperity is not necessarily a sign of divine approval—it can be just as spiritually dangerous.

All this to say, there isn’t necessarily a definitive way to say, “That’s from God, and that’s not”—except in cases where Scripture clearly forbids something. God is not telling you to marry a non-Christian. Guaranteed. God is not telling you when He will return. Guaranteed.

But aside from that, we should be gracious and give one another the freedom as Christians to test these revelations. And you only know if it was from God when He actually confirms it through an outcome, rather than just a sense of direction (if an outcome was part of the revelation that is).

Personal revelation should be treated carefully, but revelation that involves or concerns a corporate body, such as a local church, is different. In that case, there should be: More stringent criteria and more caution and consideration. For example: Who said it? From what position or office? What specifically is the content? What are our governance requirements? This is because there are more safeguards around corporate church matters and greater responsibilities given to the church body and its leadership than individuals.

Regarding personal revelation or leadings from God—the Bible is our ultimate authority in governing salvation, godliness, and holiness. But in matters of personal concern, where Scripture is indifferent, we have the freedom to test and apply discernment.

Simple, right?

Bray, G. L. (2012). God is love: A biblical and systematic theology. Crossway.

[1] Personally speaking, I can easily think of four times I’ve encountered a sort of personal revelation (I think).

- An old Pentecostal pastor once told my girlfriend at the time (though I wasn’t yet a Christian) that one day I’d be a minister. Behold, I am now a minister. (Crazy and sadly, that minister is no longer in ministry, and that girl I dated is no longer a Christian, as far as I know.)

- A strange moment while reading the Bible—I thought God was applying the Word to me specifically in ways that were highly personalized, but which I would never preach to someone else (if that makes sense). They felt like, if I can say it this way, a prophetic inkling or calling in life. I’ve never forgotten that, and I wonder about it regularly.

- A dream.

- Another dream. Boy, that one was wild!

[2] https://bigvaiandshiphrah.com/2025/02/13/entering-into-the-authority-of-the-scriptures/