As I sat down to write this, the Indian immigrant chef at my café, who serves me coffee every week, came over and asked what I was writing (side note: it is worthwhile going the same place for the same thing, to become familiar and even have the smallest of conversations). We got talking about freedom. I asked him what he thought about Australia, freedom, and the differences with India. He mentioned (without mentioning) the caste system, the authority, and living in people’s shadows until you are old enough to make decisions culturally, or get married, or work—painting the picture of a much stricter form of expectations.

But then he said (I paraphrase), “Here, there is too much freedom. For example, kids are too free to do whatever they want, and the lack of input from parents doesn’t go well for the kids.” He added, “We come from India to get a better life, but we must take the good and leave the bad of both cultures.”

I then took the opportunity to talk to him about serving God, explaining that God frees us to serve God. Bondage to God and service to God is a good thing in itself because God is good. One doesn’t need to sift through the good and bad of God and re-image him because he is perfectly good and we are perfectly safe within his service.

How much did he understand? Very little I’m sure.

But his observation about taking the good and bad from both Indian and Australian culture is illustrative of my point in this piece, that we desire freedom and autonomy at the same time that we desire boundaries and limits or a goal to direct our efforts toward.

Although autonomy is nothing to dismiss and certainly those robbed of autonomy suffer terrible plights, despite all that, even as some suffer from atrophied autonomy many ‘free’ people will suffer with hypertrophied autonomies. Many are encouraged to free themselves from shackles placed on them, metaphorically speaking, by others (either family or perhaps society at large). It’s taken that because others limit us, either by their expectations or through some sort of duty they impose on us (ie: the Indian immigrant chefs’ example), it is always an evil to be resisted in order to pursue utter self-determination and expression. In an ironic twist, this is itself a burden as shackling as the other end of the spectrum. It’s just a different ward in the same prison block. (I should have said, “welcome to Australia my Indian friend!”)

What is the factor that determines one’s freedom in this particularly ironic prison block of autonomy? It is your will. Your desire. Yet it is its own slave master. You will be bound to fulfil your own will, striving endlessly after your desires. But is our desire “our” desire? Does it really come from who you ‘really’ are? If yes, then you are obligated (ironically) to fulfil it always. But maybe we are not so naïve. Maybe we think there are times when we want to do things but don’t do them, and we do things we don’t want to do. So then, if these ‘inner desires’ are not from your ‘authentic self,’ what are they and where do they come from? What happens when you have conflicting desires? For instance, if you want to spend but also want to save. Does the stronger feeling win or does the long-term feeling win? And why?

All this illustrates the obvious: despite our desire for freedom, we are bound. We are bound no matter what. We are bound by our bodies’ limitations. We are bound by time. And most of all for many, we are bound by our own wills to be unbound.

It’s like a zip tie. The right amount of pressure gets the job done. We need enough of a boundary to operate optimally. Too loose, and things fall apart. Too tight, and function is impaired. The extremes of autonomy lead us to experience both at the same time. When we seek to be as loosely bound as possible, we are actually pulling against the noose, which only gets tighter. (Even the desire to avoid mixing metaphors due to grammatical propriety should be resisted!)

When this happens, what does it feel like? It feels like decision fatigue. Free choice, like anything, when made an idolatrous principle and blown out of proportion, becomes overwhelming and undercuts our ability to function. With theoretically limitless possibilities, we experience less satisfaction with each decision. We play the ‘what ifs,’ and the grass is always greener when fertilised by our imagination and fuelled by our discontentment (and the fertiliser is provided free of charge by advertisers—be polite and say thank you).

All this makes me wonder: how much of our world’s anxiety is related to the autonomy narrative we consume every day? Who can say for sure? But I theorise it has a significant enough impact that its effects are felt globally, especially among modern generations in the West. So, unless Alex Jones is right and the puppet masters are putting chemicals in our drinking water, we have a narrative problem—a worldview problem. With self-determination and an unrealistic view of autonomy, anxiety has more room to cause damage.

So how do you resist? You should give up your freedom. But give it up to the right master. At the same time, use your will to do his will.

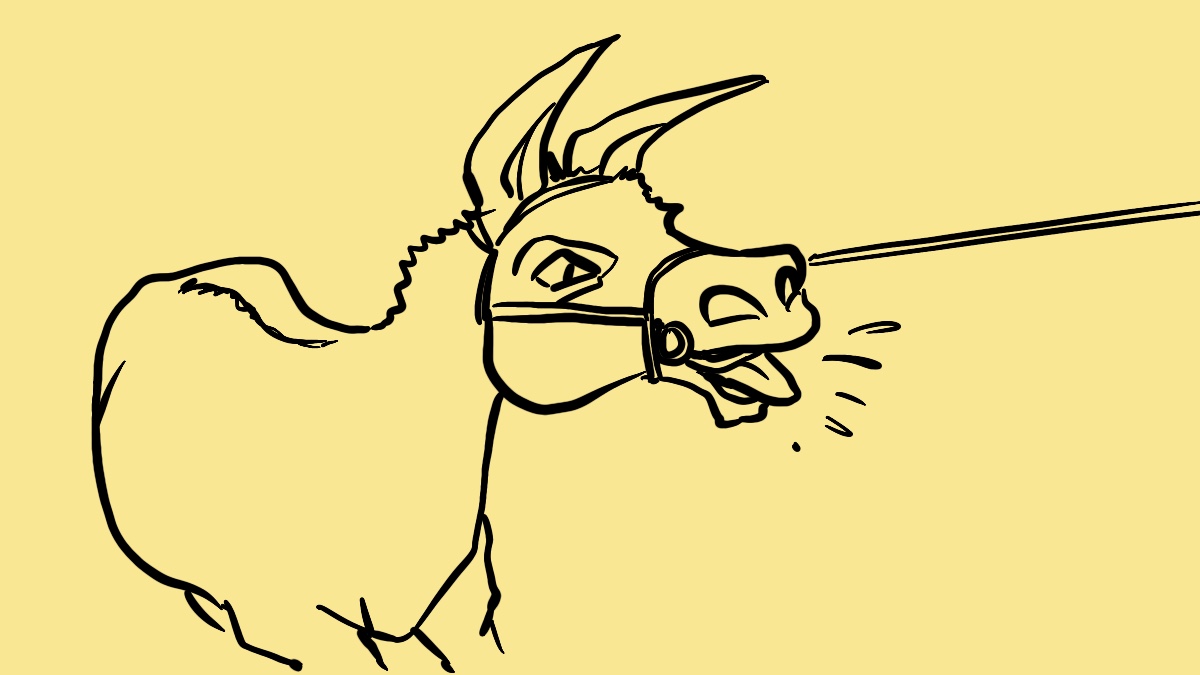

“I will instruct you and teach you in the way you should go; I will counsel you with my loving eye on you. Do not be like the horse or the mule, which have no understanding but must be controlled by bit and bridle or they will not come to you.” (Psalm 32:8-9)

This is the right way to be led by God. God’s leading is in his instruction and his teaching is through his word. His word is his loving council and this council is received willingly. So the image is that one gives up their will to follow God’s will but at the same time they use their will to follow God’s will in that they are not like an animal that kicks and resists at the leading.

This image speaks well to the religious mindset that tries to do as God says to do (because there is some sort of intellectual acknowledgement that they should) but at the same time also fights and pushes back at the leading of the Lord or grumbles and complains about it.

The meaning of the image is evocative and almost incites you to resist it. Part of us wants to fight against giving up our will for the sake of ‘dignity’ but that’s to behave like an animal (ironically). Instead, be dignified and give up your will for him.

In doing so, I think one will surprisingly find contentment.

Consider the Exodus narrative. The Israelites are freed from slavery but soon grumble and argue and are discontent with Moses (and therefore God’s leading) desiring rather to return to slavery. It is the starkest image of where our unfettered ‘autonomy’ leads us – away from God’s promises and laws and to fruitless labours in bondage to convenience.

Better by far to put all decisions through a filter of service to God because that’s what a christian is now free to do. God has freed you from the power of sin to exercise your will for his glory. So one asks when one has a choice to make, a moment that requires the exercise of their volition, “does this enable me to serve God?”

Particularly love the way this article begins. Thanks Robbie for helping us love being led by our good shepherd.

LikeLike