Today, for good reason, science stands on a tall podium. The views of scientists are often the most sought after and influential ideas in Western society. Having labels such as “scientifically proven/tested”, are sure to gain keen ears.

Again, let me state, this guy is all for science (I have a bachelor in nursing science and practiced as a registered nurse for a time). But science is also bigger than itself. The practice of science and the scientific method in the modern age have come a long way. There is history to science, there is sociology to science, and there is philosophy to science. All of which must be taken into consideration.

Our history, sociology and philosophy affect our scientific pursuits because it is from these that we ask questions of science.

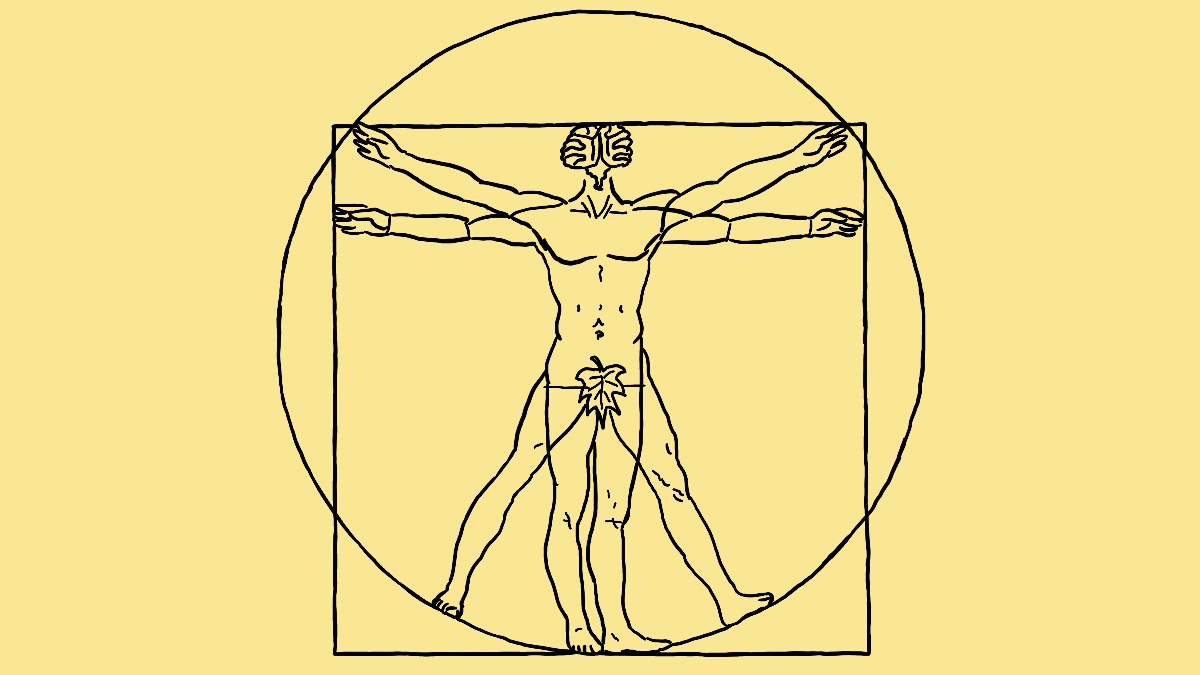

One such question that we ask science is, “what is a person?” Questions of human identity and personhood are exceedingly important to us, so it is only a matter of time before we look to science to answer this.

Scientific responses to this question tend to be physiological in nature (unsurprisingly) – we are the molecules that make up our body. Specifically however, scientists/philosophers might respond (I am thinking of people like Harris, Dennet, Pinker and the like), ‘we are our brains’. As neurons fire, memories are recalled or made, emotions are felt, actions are taken. Some look at this and say the brain is synonymous with the mind (even the person). Proponents of this view are working from a philosophical standpoint of scientism, generally speaking – which is a reductionist framework. One might say that if we can describe and explain everything to do with the ‘what’ of the brain, then we have come to the end of the grey matter regarding what a person is – it’s just that black and white.

However, when it comes to questions of personhood, we must deal with a greater scope of information and data than what science alone can interpret, while certainly taking on board all that science can illuminate. The question of personhood needs a variety of disciplines collaborating together to give a robust explanation. Sociology, philosophy, science, and theology are all involved.

For example: our jobs play a role in who we are as people, our relationships to other people play a role, as does our influence and status in society, our physical bodies dictate part of who we are, our view of who God is and therefore who we are to God (or not) plays a role (I’d argue, it is the key to unlocking the rest), our lived experience and history as a person says something about who we are.

So it is that in our search for who we are, we might be misled if our brain finds its ultimate refuge in itself. But it’s worth being aware of this stance because it’s not necessarily an uncommon one.

I think that part of the reason behind the uptake of such a view is our reliance on modern medicine. We are asking science such weighty and burdensome questions about personhood because as a society one of our prized values is our health. As science comes to solve problems that have plagued the human condition, it slowly but steadily gets a reputation for itself – ‘is there nothing that science can’t solve?’

Linked to this sentiment, we then habitually ask science to define the person (something very important to us). But it may not be such a healthy place to look for answers (if it is the only place we look for answers).

So what are you as a person? Are you just your brain? I think you know that you are more than that (or if you don’t ‘know’, you feel that you are more than that). Even as you ponder what you are, what is doing the pondering? The mind, the conscience… Is that you? Of course it is. It seems that the most complex component of all life – the physical entity of the brain – is unable to capture and sum up all the complexity of what a person is. To reduce ourselves down to the materials and mechanisms of the brain is an ironic way of dealing with the most complex organic organism known to mankind.

For me, the ever persistent presence of the mind, the first person experience, the intangible essence of a person, is one of the undeniable realities of a life that is not reducible to the material. When the arguments of scientism and materialism want to reduce you down to molecules, the conundrum of the mind fights back. Ultimately (although it is premature to discuss it now) it allows for an explanation beyond the physical. We venture into the spiritual, the transcendent, might we even say the mind after which all minds are made, God.

Sharon Dirckx. (2019). Am I just my brain? The Good Book Company.